Patriotic spirit of Daeheungsa Temple

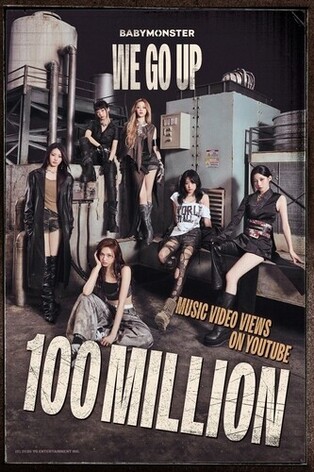

|

| ▲ Splendid view of Daeheungsa Temple in Haenam, South Jeolla Province. (Yonhap) |

Daeheungsa Temple exudes patriotic spirit of Seosan Daesa

"Eighty years ago, you were me, and eighty years since, I am you."

These are the words by Seosan Daesa (1520-1604), a prominent figure who played a key role in saving the country during the Japanese invasions in the time of Admiral Yi Sun-sin.

Seosan Daesa, moments before his interment on Myohyangsan (Mount. Myohyang), held up a portrait of himself on which he had inscribed this poem.

The inscription expresses his belief that, whether eighty years ago or in the present, we are all one. What were the consistent values in his heart? Undoubtedly, it was the spirit of patriotism, loving the people and protecting the country.

When the Japanese invasions broke out, Seosan Daesa led around 5,000 warrior-monks to the front lines, contributing to the liberation of Pyongyang and Hanyang (now Seoul) from the Japanese forces. Old or ill monks, unable to join the fight, prayed in temples to protect the nation.

Seosan Daesa urged monks across the country through official letters to stand at the forefront of the independence movement. His disciples, Samyeongdang in Pyongyang and Cheoyeong in Jirisan, fought under the command of General Gwon Yul.

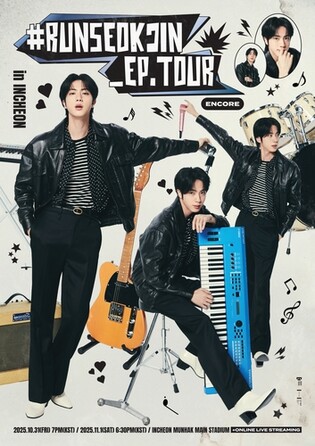

|

| ▲ From left: Cheoyeong Daesa, Seosan Daesa and Samyeong Daesa. (Yonhap) |

In the history of Buddhism, it is rare to find examples of monks actively participating in wars. Seosan Daesa embodied Buddha's wish for all the people of this land to live in peace and happiness. After the war, he handed over his official duties bestowed by the monarch to his disciple, and entered Myohyangsan to pray for the peace of the nation before leaving this world.

He left his “uibal” -- known as a combination of "gasa (clothes) and "balwu (utensils) -- at Daeheungsa Temple in Haenam as a testament instructing his followers to preserve his teachings, scriptures, and ceremonial instruments. He referred to Daeheungsa Temple as the place of “samjae bulyipjicheo (place where the three disasters cannot enter)” and “manse bulhwejiji (a land unharmed for ten thousand years),” and designated it as a sanctuary from wars and other calamities.

In Buddhism, a monk's uibal symbolizes the ethical precepts passed down from a master to his disciples. Other precious artifacts, such as the golden ceremonial bowl, jade begging bowl, eating utensils, and ceremonial robes bestowed by the monarch, were moved to Daeheungsa Temple.

With the migration of hundreds of disciples, Daeheungsa Temple transformed into a patriotic temple inheriting the teachings of Seosan Daesa. Seosan's teachings are exhibited at the Daeheungsa Temple Sacred Relics Museum.

|

| ▲ These photos show King Seonjo's royal edict of appointing Seosan Daesa as the commander of the warrior monks (L) and the utensil and shoes used by Seosan Daesa. (Yonhap) |

In an effort to wash away the disgrace of the Imjin War (Japanese invasion) and the Byungjahoran (Qing invasion), King Jeongjo sought to strengthen the nation by widely promoted the loyalty and integrity of Seosan Daesa.

In 1798, the king ordered the construction of Pyochungsa Temple within the grounds of Daeheungsa Temple to commemorate Seosan.

The epitaph at Pyochungsa, where the portraits of Seosan Daesa, Samyeong, and Cheoyeong Daesa are enshrined, bears the handwritten seal of King Jeongjo.

Pyochungsa annually conducts Confucian-style memorial rites for Seosan Daesa during spring and autumn.

In 2018, UNESCO inscribed Daeheungsa Temple as a World Cultural Heritage site along with Yangsan Tongdosa, Yeongju Buseoksa, Andong Bongjeongsa, Boeun Beopjusa, Gongju Magoksa, and Suncheon Seonamsa.

King Jeongjo recognized the importance of Seosan Daesa's memorial rites, praising the coexistence of Buddhist and Confucian cultures.

But why did Seosan designate Daeheungsa Temple as the successor temple?

In his youth, having visited Duryunsan and Daeheungsa, Seosan explained to his disciples that Haenam had fertile soil, abundant resources, and was a desirable place to live, away from the political turmoil of Hanyang (Seoul). Having almost lost his life during the Jeongyeorip conflict, where he was unfairly targeted, Seosan believed that to escape political strife and power abuse, it was good to remain distant from the center of politics.

After inheriting Seosan's teachings, Daeheungsa Temple prospered significantly. In the late Joseon period, Daeheungsa anointed 13 chief monks and 13 high-ranking monks.

A temple that preserves “the Buddha (Bulbo),” “the Dharma (Beopbo),” and “the Sangha (Seungbo)” is honored as “sambo sachal (temple of three treasures).”

|

| ▲ The nightly view of Daeheungsa Temple. (Yonhap) |

Some of the famous sambo sachals include Tongdosa Temple with the bodily relics of Shakyamuni Buddha; Haeinsa Temple with the Tripitaka Koreana; and Songgwangs Temple that dubbed 16 national monks during the Goryeo era.

Some perspectives regard Songgwangsa as a prominent Seungbo Temple of Goryeo, and Daeheungsa, which produced outstanding monks in the late Joseon period, as a Seungbo Temple of Joseon.

To continue Seosan's legacy, a Patriotic Great Hall (Hoguk Daeseongjeon) is being constructed at Daeheungsa. After seven years of construction, the building phase has recently concluded, with an additional three years expected for internal solemnity.

The Patriotic Great Hall, if completed, is set to become the largest wooden Buddhist structure in the country. The hall will include an altar to honor the patriots who sacrificed their lives for the nation, such as those who perished during the Imjin War, Japanese colonial rule, the Korean War, and the Democracy Movement.

Amid Japan’s repeated claims over sovereignty regarding Dokdo, memories of the Imjin War are incessantly being revisited. The Korean War that claimed the largest human lives in Korean history and the unfinished armistice have intensified the fervent desire for patriotism. The completion of the Patriotic Great Hall, a testament to that aspiration, is eagerly awaited.

|

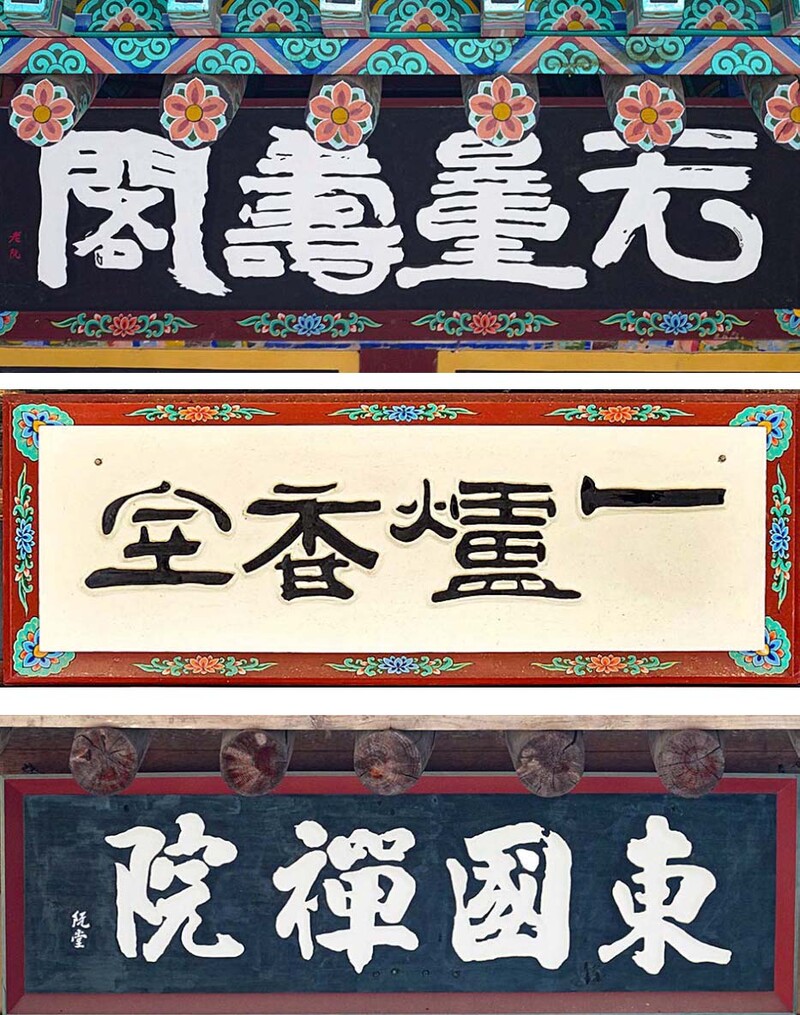

| ▲ The epitaphs in Daeheungsa Temple, written by Chusa Kim Jeong-hee. (Yonhap) |

The templates of Daeheungsa Temple

A Korean temple is not just a place of worship for a specific religion. Over a long history, Buddhism and Confucianism have formed the two major pillars of Korean spirituality and culture. As a result, temples have become stages and cradles where history, culture, and art unfold.

Large temples are rich in Buddhist cultural assets and historical relics. Among them, Daeheungsa Temple, particularly known for its abundant literary and artistic works, offers a vivid experience of artistic brilliance and the whirlwind of history.

An unforgettable tale is woven between the eminent calligrapher Chusa Kim Jeong-hee (1786-1856), Confucian scholar Wongyo Lee Gwang-sa (1705-1777), and Chouiseonsa (1786-1866), who was a close friend of Chusa.

Lee Gwang-sa, a member of the royal family and a prominent scholar, completed Donggukjinche, the unique Korean calligraphy style. He was the father of Lee Geung-ik, the author of "Yeonlye Silgisulgeol," which emphasized facts over personal opinions, evaluating history solely based on objective observations.

Involved in factional disputes and conspiracy, Lee Gwang-sa spent 23 years in exile, eventually passing away on Shinjido Island in Wando.

His writings, including the epitaph written by Wongyo, are displayed throughout Daeheungsa, including Daeungbojeon, Chimgyeroo, Haetalmoon, and Cheonbuljeon.

Chusa, born about 80 years after Wongyo, visited Daeheungsa on his way to exile in Jeju. He demanded that Wongyo's epitaph be taken down, claiming Wongyo had ruined Korea's writing style. Chouiseonsa insisted on the removal of Wongyo's epitaph and, instead, hung the epitaph for "Muryang Sugak," written by Chusa.

A few years later, when Chusa was released from exile and headed to Hanyang (Seoul), he met Chouiseonsa again, admitting that his previous thoughts were narrow-minded. He requested the epitaph written by Wongyo to be hung once more.

|

| ▲ The epitaphs in Daeheungsa Temple, written by Changam Lee Gwang-sa. (Yonhap) |

The plaques for "Dongguksunwon," where Chouiseonsa resided, and "Illohyangsil" at Ilji-am, where Chouiseonsa lived, are among the calligraphy works left by Chusa at Daeheungsa.

The epitaph "Gaheoru" above the entrance of Cheonbuljeon was written by Changam Yi Sam-man (1770-1847), considered one of the three master calligraphers of the late Joseon period.

Born into poverty, Changam learned calligraphy through self-study, using brushes made from arrowroot. Chamgam sought out Chusa on exile to Jeju, asking Chusa for an evaluation of his writing.

Chusa, 16 years younger than Changam, remarked that Changam’s writing “would help him barely make his ends meet in the rural society. This incident reflects Chusa's sense of elitism.

After his release from exile, Chusa visited Changam, only to find that Changam had already passed away. Chusa wrote an epitaph for Changam's tombstone, stating, “A great calligrapher who lived a lifetime for the sake of writing lies here. Let future generations not defile this grave. His virtuous brushwork reached the highest peak, and his fame extended even to China.”

|

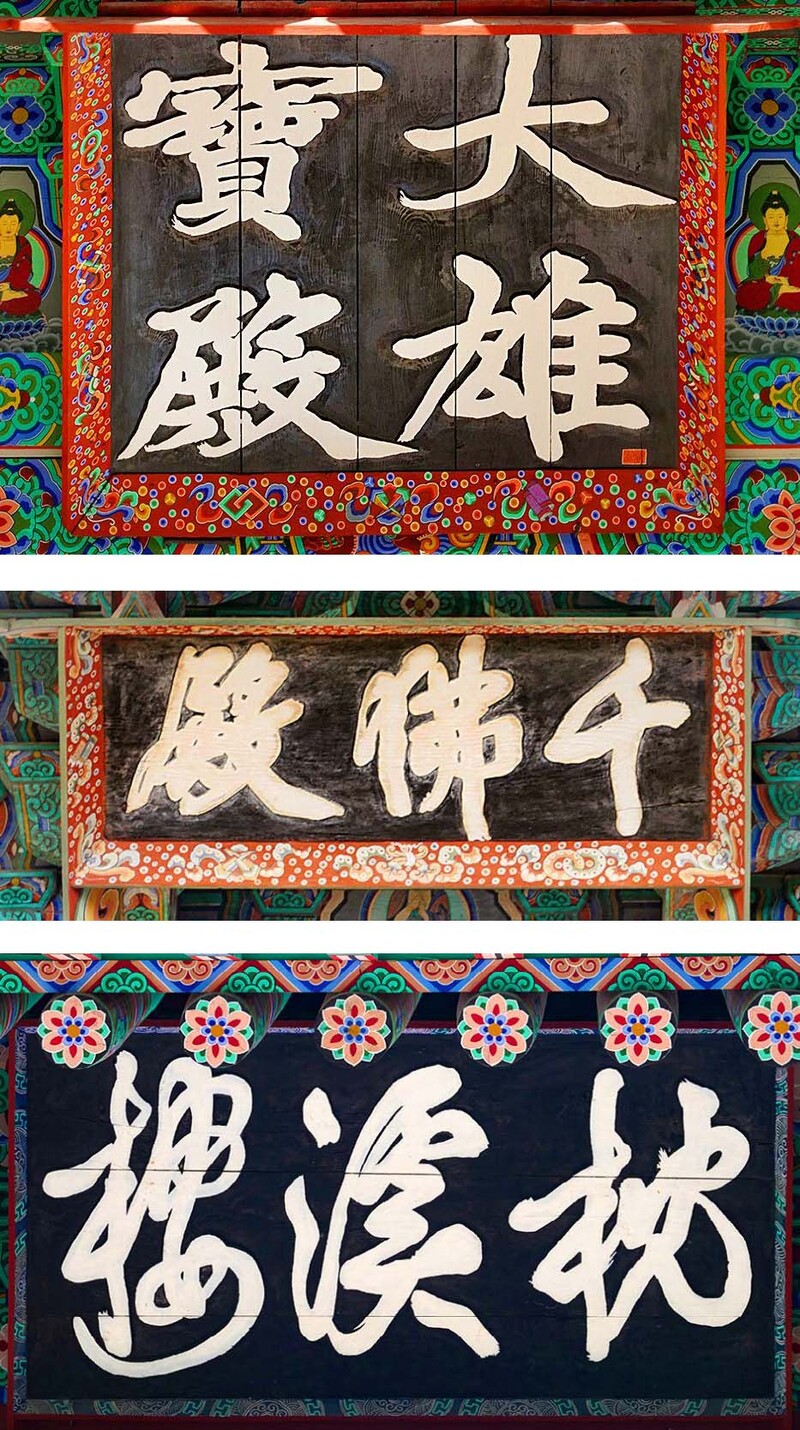

| ▲ A statue of Chouiseonsa at Daeheungsa Temple. (Yonhap) |

The 13th head monk, Chouiseonsa, is renowned as the writer of Korea’s first book on local tea ceremony, titled “Dongdasong.” He is praised as the “great sage” in Korea.

A poet, artist, calligrapher, and scholar, Chouiseonsa had deep knowledge in various fields, including Confucianism, Taoism, and other studies. He interacted with contemporary scholars such as Dasan Jeong Yak-yong during his exile in Gangjin.

Leading the revival of Daeheungsa Temple, Chouiseonsa, in his later years, built Iljiam on the midsection of Duryunsan Mountain, where he sought refuge. The term “Ilji” is derived from a line in a poem, meaning “a magpie is content with just one branch.”

Sochi Heonyeon, a renowned artist of Namjong painting, was a disciple of Chouiseonsa. Chouiseonsa introduced Sochi Heonyeon to Chusa and, in turn, Sochi learned ink painting from both Chouiseonsa and Chusa. The Daeheungsa Museum displays calligraphy and paintings by Chouiseonsa, a portrait of Chouiseonsa painted by Sochi, and Sochi's ink paintings. King Jeongjo's powerful epigraph for Pyochungsa is also prominently featured.

Next to this epigraph is a plaque for “Eoseogak,” written by Chusa's disciple Widaeng Sin Gwan-ho. It means a hall with the calligraphy of the king.

Pyochungsa, adorned with the king's signature, serves as a guardian deity protecting Daeheungsa from disdain and oppression by the ruling class. The epigraph for Daegwangmyeongjeon, built to pray for Chusa's safe return from exile in Jeju, was also written by Sin Gwan-ho.

Modern calligraphers such as Gangam Songsungyong, Yeocho Kim Eung-hyun, and Unam Joyongmin have their signature plaques displayed at Daeheungsa, including Yeonhamun, Iljiam, and Iljumun.

As one raises one’s head, the epigraphs become evidence of fervent artistic spirits and provide clues to reading history.

Mount. Duryunsan facing Mount. Halla

Entering the grounds of Daeheungsa, one is immediately captivated by the gentle ridgeline of Duryunsan surrounding the temple.

It even gives a sense of déjà vu, as if showing similar landscape elsewhere. The eight ridges and nine peaks of Duryunsan, known as Gugok Palbong, create a basin in the center, with Daeheungsa situated magnificently. When viewed from above, the eight peaks resemble a miniaturized version of Mount Baekdu, the axis of heaven and earth. If Duryunsan is likened to a lotus, Daeheungsa sits at the center like a flower bud.

Duryunbong (630 meter), Garyeonbong (703 meter), Noseungbong (685 meter), Gogyebong (638 meter), Hyangrobong (469 meter), Hyeolmangbong (379 meter), Yeonhwabong (613 meter), and Dosolbong (672 meter) encircle Daeheungsa Temple. When standing atop Noseungbong, distant Hallasan rises above the clouds to the south.

Park Chung-bae, the former head of Daeheungsa Museum who has climbed Duryunsan over ten times, expressed joy at seeing Mount. Halla (“Hallasan”) for the first time. To the north, the famous peaks of Wolchulsan and Cheongwansan are visible, and the seas in front of Gangjin, Mokpo, Wando, and Jindo unfold in a mesmerizing, azure panorama.

Looking down from the Daeheungsa courtyard, Duryunbong, Garyeonbong, and Noseungbong resemble the figure of a lying Buddha.

Duryunsan appears like a gentle dirt mountain at first glance, but the actual climb through the rocky sections, akin to the peaks of Bukhansan or Seoraksan, proved challenging. The ridge trail was narrow with steep cliffs on both sides.

Despite the installation of wooden deck stairs to ensure safety, the path featured iron footholds for stability and iron grips embedded in the rocks for hand support. Even on a weekday, hikers steadily continued, revealing Duryunsan's popularity among climbers.

At the site of Manilam, where the first hermitage was built by Daeheungsa, a five-story stone pagoda from the mid-Goryeo period, estimated to have been constructed, stood leaning slightly, awaiting preservation. Not far from there, stands a Japanese nut tree, estimated to be around 1,200 to 1,500 years old. This so-called "thousand-year tree" displayed well-balanced branches, showcasing exceptional vitality. Maintaining balance for a millennium is no easy feat for any life form.

The thousand-year tree is associated with the legend of the North and South Maitreya Buddha statues, known as Bukmireukam and Nammireukam.

In the heavenly realm, a celestial man (“cheondong”) and a celestial maiden (“cheonnyeo”) were expelled for breaking a precept. To return to the heavens, they had to carve Buddha statues on rocks within a day. To accomplish this, they tied the sun to this tree with a rope and started sculpting. The celestial maiden decided to carve a seated Maitreya on the North Maitreya Rock, while the celestial man chose to carve a standing Maitreya on the South Maitreya Rock.

The celestial maiden completed the Maitreya Buddha first but grew tired of waiting for the celestial man. Exhausted, she cut the rope and ascended to the sky alone. The celestial man could never ascend to the heavens and became a deity on Earth, according to the legend.

The North Maitreya Buddha statue is a masterpiece of Korean Buddhist sculpture, inheriting the style of the golden age of the 8th century. Designated as a national treasure, it exudes benevolence and richness of expression.

In comparison, the South Maitreya Buddha statue is an unfinished work, engraved on a large cliff in a less conspicuous location. Weathering made it challenging to discern the sculpture's form.

Quietly etched on an isolated and majestic rock, the South Maitreya Buddha seemed to represent the countless lives that come and disappear in silence.

(C) Yonhap News Agency. All Rights Reserved

![[가요소식] 보이넥스트도어, 신보로 3연속 밀리언셀러 달성](/news/data/20251025/yna1065624915905018_166_h2.jpg)